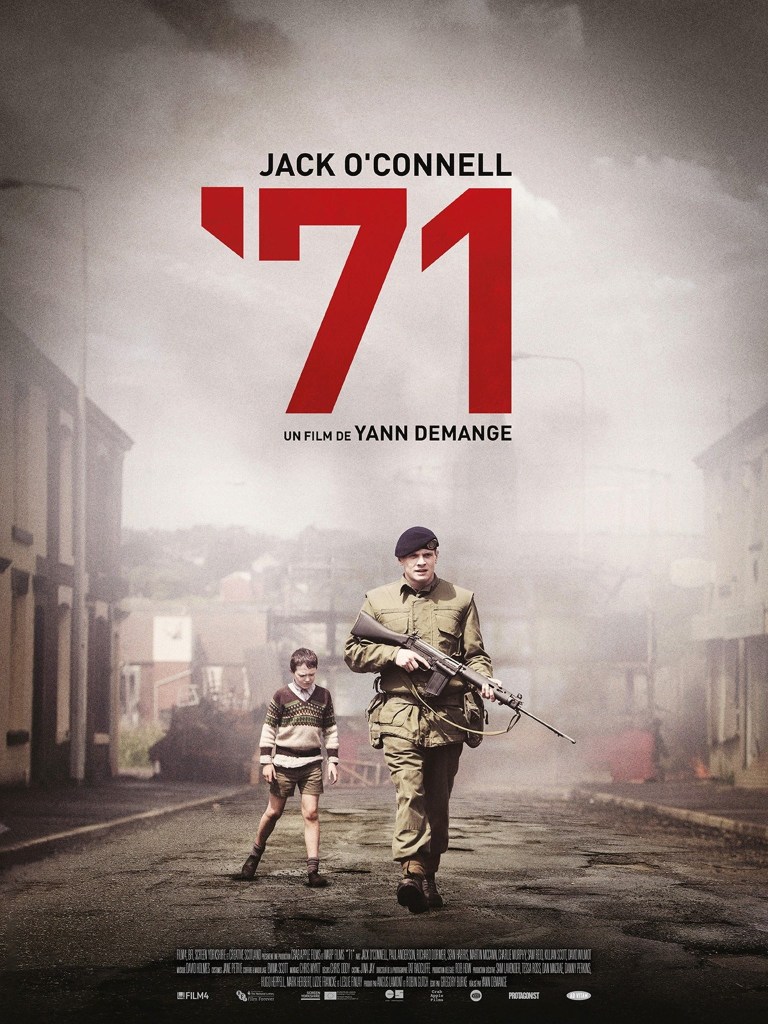

Synopsis- A young British soldier is accidentally abandoned by his unit during a riot in Belfast. Alone behind enemy lines, he must navigate a nightmarish urban warzone while pursued by multiple factions with murky motives and deadly intentions.

Director- Yann Demange

Cast- Jack O’Connell, Sean Harris, Paul Anderson

Genre- Historical, Thriller, War, Drama

Released- 2014

The Warriors meets the troubles, Yann Demange’s ’71 is a taut, lean thriller that crackles with urgency and paranoia, transforming the fractured streets of Belfast into a hostile battlefield of shifting allegiances and blurred morality. Part political drama, part survival story, it’s a film that manages to be both grounded in a specific historical moment and universally compelling as a portrait of one man’s harrowing ordeal.

Set during the height of the Troubles, ’71 follows a single day and night in the life of Private Gary Hook (Jack O’Connell), a new recruit with the British Army deployed to Northern Ireland. When a routine house search turns into a chaotic riot, Hook is separated from his unit and left stranded in a hostile city. What follows is a nerve-shredding journey through alleyways, safe houses, and backroom deals, as Hook tries to survive the night while forces on all sides, IRA factions, Loyalist paramilitaries, and British military intelligence, pursue their own brutal agendas.

O’Connell, coming off his breakthrough in Starred Up, though I first came accross him in British teen drama Skins, delivers a quietly riveting performance. His Gary Hook is neither hero nor automaton; he’s a frightened, resourceful young man, reactive rather than proactive, swept along by a tide of violence he barely understands. There’s little exposition, little hand-holding, and no grand speeches. Demange wisely favours visual storytelling, and O’Connell does much with silence, his expressive face reflecting terror, disbelief, and grim determination.

Demange’s direction is masterful in its restraint. The film has the raw immediacy of a documentary but the sleekness of a well-crafted thriller. Cinematographer Tat Radcliffe shoots the streets of Belfast with a washed-out palette and a kinetic handheld style that brings the tension close to breaking point. The violence, when it erupts, is sudden and ugly, shocking not for its gore but for its realism and ambiguity.

What sets ’71 apart from many war or political thrillers is its refusal to paint in absolutes. There are no clean villains or noble saviours here. The British Army is shown to be as divided and compromised as the groups they are fighting. Intelligence operatives play a duplicitous game with deadly consequences, while factions within the IRA are depicted as both freedom fighters and cold-blooded executioners. Demange never loses sight of the human cost, avoiding moral sermonising in favour of observation and nuance.

If the film falters slightly, it’s in its final stretch, where narrative contrivance creeps in and the emotional payoff, though satisfying, feels somewhat conventional after such a daringly ambivalent setup. But these are minor quibbles in a film that otherwise pulses with immediacy, clarity, and purpose.

’71 is a rare achievement: a war film that thrills without glorifying, a political film that provokes without preaching. Anchored by a superb performance from Jack O’Connell and directed with muscular precision, it’s a powerful, absorbing watch.

Leave a comment