Synopsis- When a young chauffeur marries a wealthy heiress and builds their dream home on cursed land, their romantic idyll begins to crumble under the weight of secrets, suspicion, and something sinister that may not be entirely of this world.

Director- Sidney Gilliat

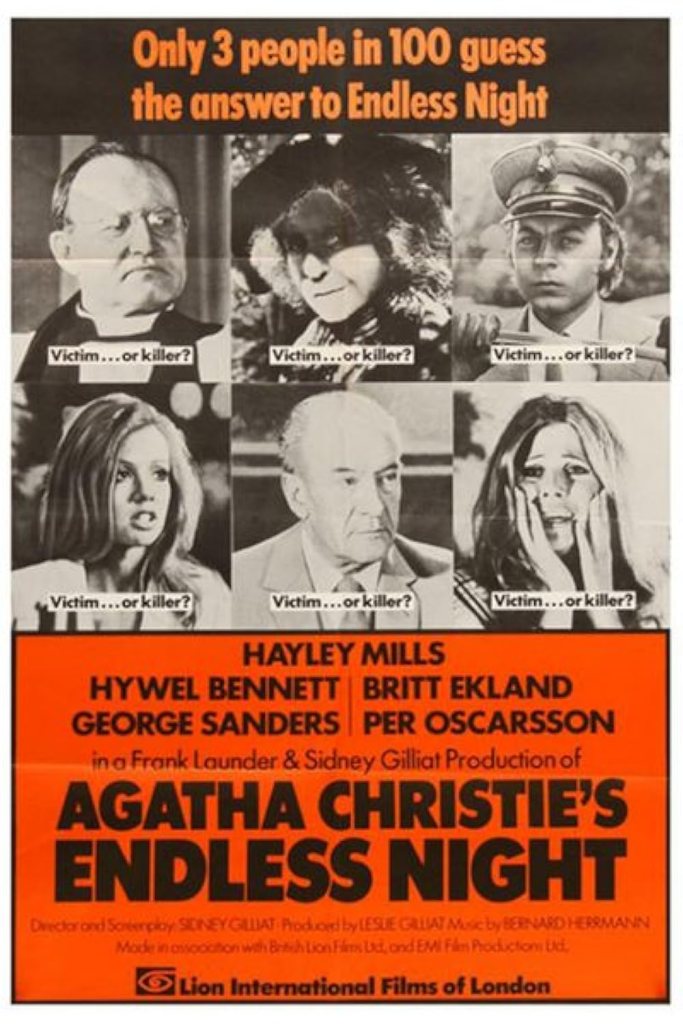

Cast- Hywel Bennett, Hayley Mills, Britt Ekland

Genre- Mystery, Psychological Thriller, Drama

Released- 1972

Sidney Gilliat’s Endless Night (1972) is that rarest of Agatha Christie adaptations: one that eschews the comfort of parlour room deductions and embraces an atmosphere of creeping dread. Released during a period of cinematic experimentation, the film blends classic mystery elements with a distinctly ‘70s psychological edge, creating a tense and disorienting experience that lingers long after the final frame.

At first glance, this appears to be one of Christie’s more romantic tales: Michael Rogers (Hywel Bennett), a restless working-class dreamer, falls in love with the wealthy and fragile heiress Ellie Thomsen (Hayley Mills). The couple escape to Gipsy’s Acre, a parcel of land steeped in legend and unease, where they commission the eccentric architect Santonix (Per Oscarsson) to build their modernist sanctuary. But paradise proves precarious, and the film deftly charts its descent into paranoia and darkness.

Bennett delivers a measured performance as Michael, capturing both his charm and the disturbing sense that he’s not quite what he seems. Hayley Mills, in a far more adult and emotionally layered role than audiences were accustomed to, is compelling as Ellie, exuding a vulnerability that is both tragic and suspicious. Their chemistry is intentionally uneasy, the tension simmering just beneath the surface of domestic bliss.

Britt Ekland provides a sultry, ambiguous counterpoint as Greta, Ellie’s companion whose sudden reappearance unsettles the household. George Sanders, in one of his final screen roles, lends gravitas as the cynical lawyer Andrew Lippincott, and Lois Maxwell, far removed from her Miss Moneypenny persona—adds further intrigue as Ellie’s aloof stepmother.

Gilliat, better known for co-writing The Lady Vanishes, directs with a steady hand, favouring slow burns over sudden shocks. The mood is eerie rather than lurid, aided by Harry Waxman’s cold, sun-dappled cinematography and Bernard Herrmann’s gorgeously ominous score, which evokes a sense of fate closing in. The film’s dreamlike pacing and jarring tonal shifts might disorient some viewers, but they serve the story’s escalating psychological tension.

While traditional Christie purists may miss the tidy resolutions and formal elegance of her detective stories, Endless Night proves her work can adapt to darker, more introspective terrain. The screenplay, also penned by Gilliat, strips back exposition in favour of ambiguity, trusting the audience to pick up on subtext and shifting loyalties.

What ultimately elevates Endless Night is its refusal to categorise itself neatly. It is part gothic romance, part psychological thriller, and part modernist horror. The twist, when it arrives, is not merely clever but devastating—less a “gotcha” moment than the final turn of the screw in a slow, unrelenting spiral.

With its unsettling tone, strong performances, and haunting style, Endless Night is a bold and underrated adaptation that stands among the most artistically ambitious Agatha Christie films. A stylish, chilling gem of 1970s British cinema.

Leave a comment