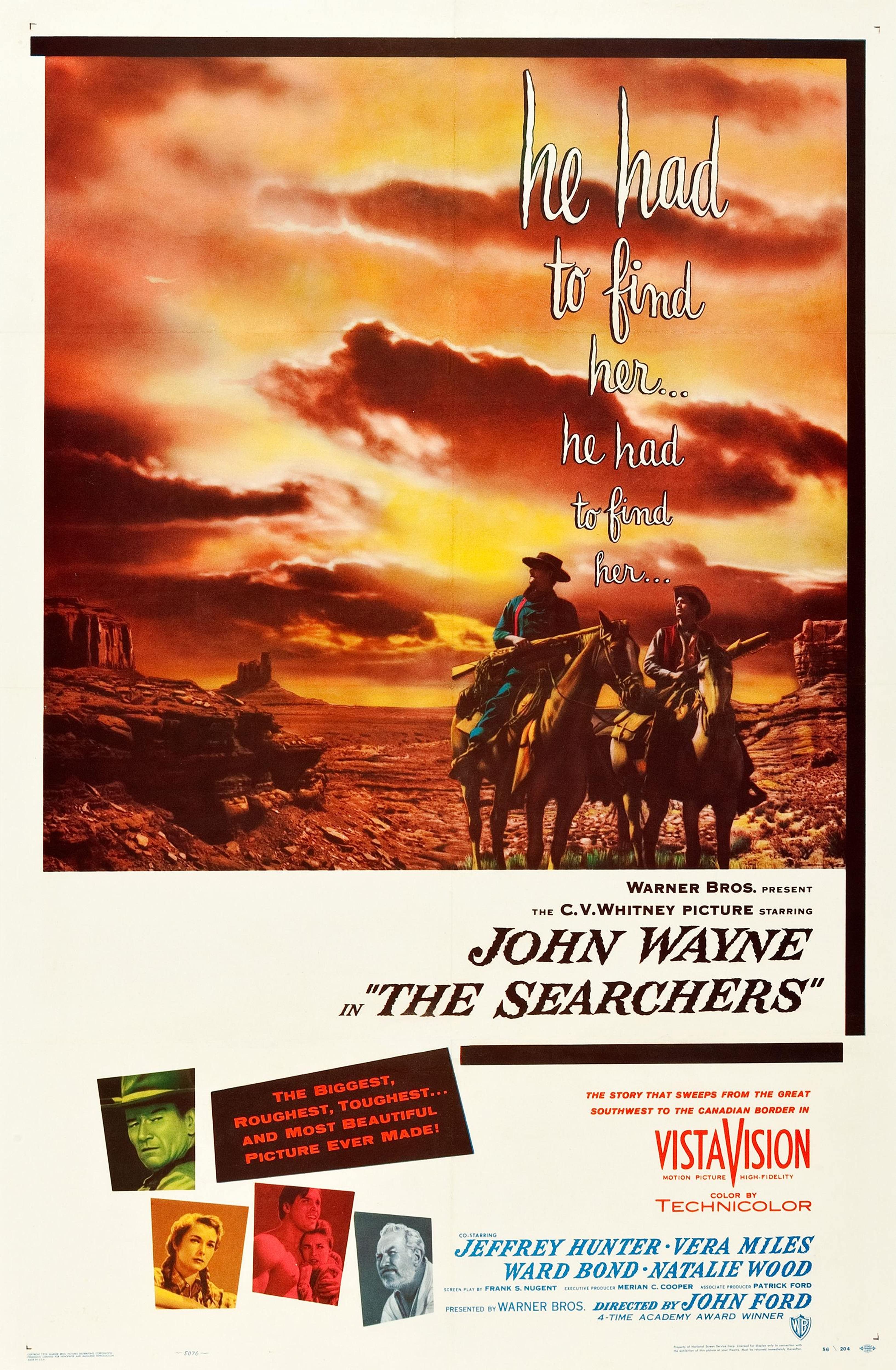

Synopsis- When ex-Confederate Ethan Edwards spends years hunting his kidnapped niece, his obsessive quest across frontier landscapes exposes prejudice, obsession, and moral ambiguity in John Ford’s haunting Western

Director- John Ford

Cast- John Wayne, Jeffrey Hunter, Vera Miles, Natalie Wood

Released- 1956

There are great Westerns, and then there is The Searchers. Directed by the incomparable John Ford, this isn’t merely a film about cowboys and Indians, but a psychologically layered exploration of obsession, racism, and the myth of the frontier itself. On the surface, it’s the story of Ethan Edwards (Wayne), an embittered ex-Confederate soldier who returns to Texas only to see his family slaughtered and his niece abducted by Comanches. He embarks on a years-long odyssey to rescue her, accompanied by his part-Cherokee nephew Martin (Hunter). That’s the plot. But beneath that familiar Western framework lurks something far more unsettling.

John Ford’s mastery of the genre is well established, yet here he turns the Western inside out. His Monument Valley vistas, shot in rich VistaVision, are dazzling, almost mythological in their beauty, yet Ford undermines that beauty with a protagonist who is anything but heroic. Wayne’s Ethan is one of cinema’s most fascinating anti-heroes: magnetic, charismatic, but steeped in hatred. His casual racism and merciless streak make him both repellent and riveting. This was, and still is, a seismic shift in how audiences view the archetypal Western hero. Wayne himself considered Ethan his most complex role, and it’s not hard to see why.

What’s remarkable, rewatching The Searchers nearly seventy years later, is just how modern it feels. The plot isn’t a comforting tale of triumph; it’s a troubling character study that refuses easy resolutions. Natalie Wood’s Debbie, the kidnapped niece, becomes less a prize to which will be won back and more a mirror reflecting Ethan’s terrifying obsession. The longer the journey continues, the more we realise this isn’t simply about “rescue”, it’s about whether Ethan will save or destroy her.

Ford counterbalances this darkness with moments of warmth, humour, and humanity. Jeffrey Hunter’s Martin is the moral centre: young, compassionate, and increasingly appalled by his uncle’s fanaticism. Vera Miles brings emotional heft as Laurie, grounding the narrative in something resembling normal human relationships amidst the bloodshed and vengeance. But it’s that final shot, the famous closing doorway, that lingers in the mind. Ethan stands framed, alone, forever outside the family and the home he cannot enter. It’s one of the most poignant images in American cinema.

I firmly believe that a great film changes every time you revisit it, and The Searchers epitomises that. What once looked like a sweeping Western adventure now plays as an uneasy critique of the very myths it helped to cement. It’s big, bold, and breathtakingly beautiful, but also haunting, ambiguous, and uncomfortable.

For all its grandeur, The Searchers is not an easy watch, nor should it be. It is a masterpiece that forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about violence, prejudice, and obsession.

Leave a comment