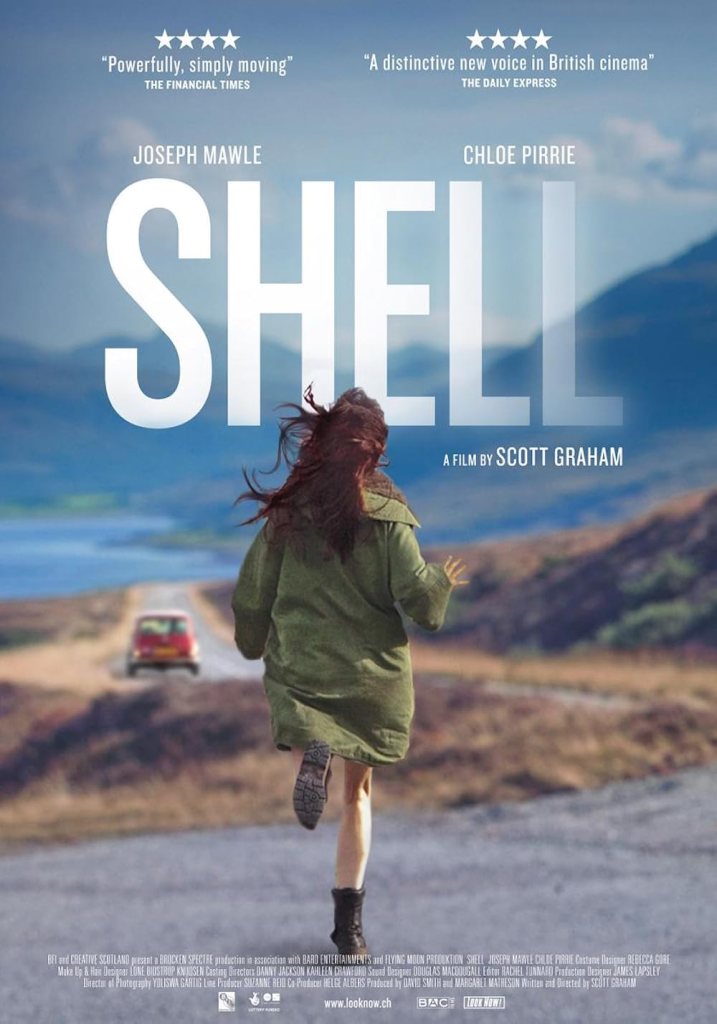

Synopsis- Set against the striking backdrop of the Scottish Highlands, Shell follows a teenage girl living a solitary existence with her reclusive father at a lonely petrol station. As their isolated world begins to fracture, the film delves into themes of loneliness, longing, and the complicated web of human emotions.

Director- Scott Graham

Cast- Chloe Pirrie, Joseph Mawle, Iain De Caestecker

Genre- Drama, Psychological, Coming-of-Age

Released- 2012

In Scott Graham’s Shell, the stark beauty of the Scottish Highlands becomes more than just a setting; it mirrors the profound sense of isolation experienced by the film’s characters. This is a film that favours silence over speech; its emotional resonance emerges not from dialogue, but from the nuanced, unspoken interactions between its two central figures: Shell (Chloe Pirrie), a 17-year-old girl bound to the desolation of a petrol station, and her father Pete (Joseph Mawle), whose protectiveness borders on obsession.

Graham’s directorial style is spare yet profoundly meditative, with the wild landscape acting almost as a character in its own right. The cinematography captures the harsh, wind-swept terrain in muted greys and soft, natural light, creating a poignant atmosphere that feels both raw and intimate. Each frame seems imbued with emotion, akin to the works of Lynne Ramsay or early Andrea Arnold, where the power lies in the stillness and observation of life. The camera lingers on small details, a lingering glance, a moment of hesitation, and these silent exchanges bubble with unexpressed meaning.

Chloe Pirrie’s performance as Shell is nothing short of extraordinary. Her wide-eyed vulnerability encapsulates the tumultuous nature of adolescence; she embodies a girl caught between a desire for connection and a haunting fear of what that connection might bring. Her portrayal captures the spirit of youth perfectly, as she grapples with the conflicting impulses of intimacy and independence. Meanwhile, Joseph Mawle’s performance as Pete is equally compelling, characterised by a haunting restraint. He portrays a father whose love is undeniably deep yet is suffocating in its intensity. Their bond is fraught with tension; it teeters on the brink of comfort and discomfort, revealing the complexity of their mutual dependence.

However, despite the strengths of the acting and cinematography, the script sometimes falters. The motivations of the characters, while layered, occasionally lack clarity, leaving viewers wanting to delve deeper into the complexities of their internal struggles. At times, the film’s pronounced focus on mood can lead to stretches that feel sluggish, with emotional revelations dulled by repetitive scenes. The minimalism, although beautifully crafted, may leave some audiences feeling somewhat disconnected, as the narrative pace can feel too languid for those seeking a more traditional progression.

Yet, it’s evident that Shell commands respect for its subtle storytelling and genuine emotional courage. It trusts in the power of silence and the natural landscape to convey its story, often achieving moments of profound resonance where the desolation of isolation feels almost tangible. While Graham’s debut may not fully reach the heights it aspires to, it establishes him as a filmmaker of remarkable restraint and insight, one who recognises that sometimes the most profound truths are found in the quietest moments.

Leave a comment