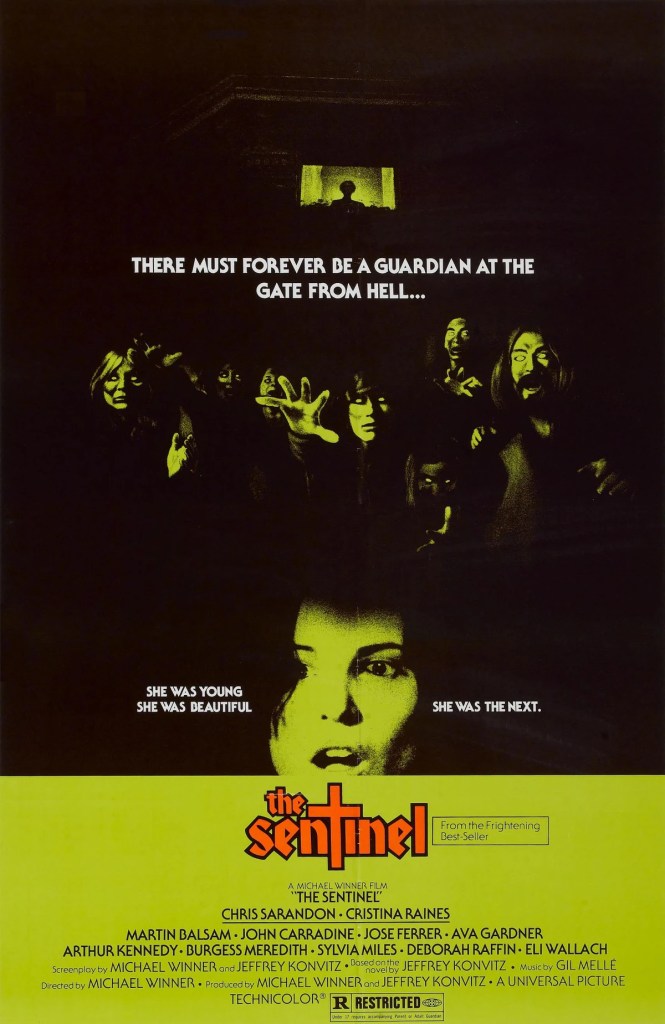

Synopsis- After numerous failed suicide attempts, a depressed fashion model moves into a new home. However, she soon begins to experience strange and horrific delusions.

Director- Michael Winner

Cast- Cristina Raines, Chris Sarandon, Ava Gardner, Burgess Meredith, Sylvia Miles, Eli Wallach, Beverly D’Angelo, John Carradine

Released- 1977

There’s something irresistibly grimy and seductive about The Sentinel, Michael Winner’s 1977 dip into the supernatural. It’s the sort of film that feels as though it has been dredged from the gutter of 1970s New York, carrying with it the anxieties, neuroses, and grubby textures of a city in decline. Winner, was never known for subtilty, instead leaning heavily into the lurid possibilities of Jeffrey Konvitz’s novel, creating a horror film that is by turns elegant, exploitative, and sticks to you like grime.

Cristina Raines, in a performance that’s more compelling than it’s often given credit for, playing Alison Parker, a successful model with a traumatised past and a perilously fragile sense of self. When she moves into an apartment in Brooklyn, a building that screams New York and more than likely goes for a couple of million these days. Settling into a rhythm of escalating weirdness as if Rosemary’s Baby (1968) meets Twin Peaks. Her neighbours include a flamboyantly intrusive Burgess Meredith, a spectral-looking Sylvia Miles, and a mute Beverly D’Angelo whose presence manages to be both comic and nightmarish. It is, unmistakably, a building populated by failed saints, fallen creatures, and the damned.

Winner’s direction is often derided as blunt, but here that bluntness becomes a kind of aesthetic strategy. The film moves with the unsettling logic of a nightmare: scenes begin too abruptly, conversations leave you feeling slightly ‘off’, and the camera lingers on faces, always faces, long enough for the uncanny to seep in. There’s a genuine commitment to discomfort, and Winner’s New York is not the cinematic playground of Woody Allen or Sidney Lumet; it’s a purgatorial landscape where glamour curdles at the edges.

The supporting cast is an embarrassment of riches. Ava Gardner appears with the effortless hauteur of someone who doesn’t need to prove anything. Chris Sarandon lends a slippery charm to the boyfriend who may, or may not, have Alison’s best interests at heart. John Carradine, as the blind priest who sits perpetually at the top floor, becomes a chilling symbol of spiritual exhaustion: the sentinel of the title, worn down by a job no earthly person should want.

Of course, The Sentinel is not without its controversies, including Winner’s gleeful flirtation with exploitation and an infamous climax involving real people with physical deformities which wouldn’t fly today. Even viewed through a contemporary lens, it’s an unsettling choice, provocative in ways that feel both ethically dubious and thematically pointed. Whether one considers it transgressive art or crass sensationalism may depend on one’s own tolerance for 1970s horror’s habit of crossing lines simply because it could.

Still, the film endures because beneath its tawdry surfaces beats a surprisingly mournful heart. It’s a story about guilt, temptation, and the crushing weight of redemption, a Grand Guignol morality play staged against the cracked facades of New York’s decaying elegance. For all its excess, The Sentinel lingers. It unnerves. And in its demented, unrepentant way, it dazzles.

Leave a comment